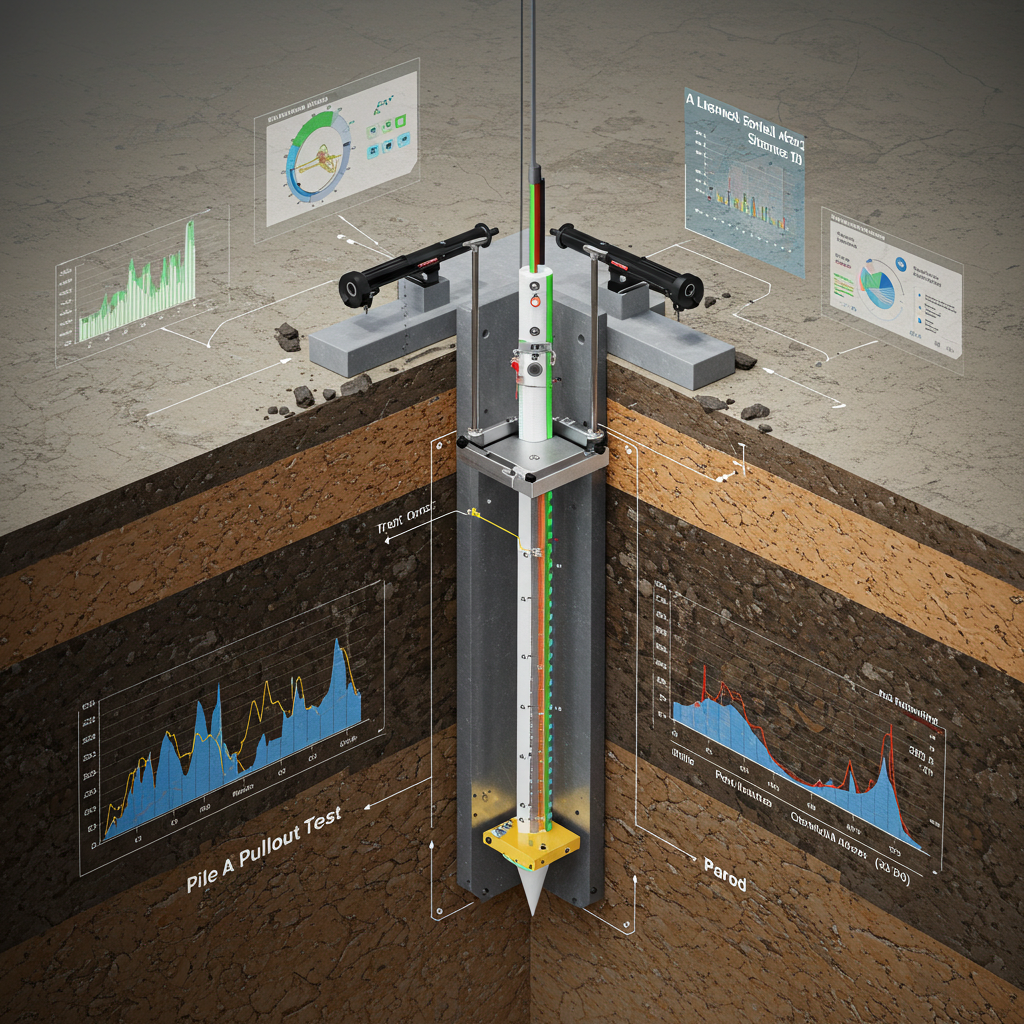

Effective anchoring is crucial for the safety and stability of emergency shelters during natural disasters. Inadequate anchoring can create significant risks for affected communities. Small anchors have emerged as a practical and portable solution. They provide lightweight support to temporary structures like tents, ensuring quick setup and safety for disaster victims. Additionally, these small anchors are commonly used in outdoor activities such as expeditions and camping, offering a reliable support system.

Ground anchors stabilize temporary tents by ensuring a secure connection between the ground and the tent structure. In emergency relief situations, these anchors facilitate the rapid installation of relief camps for rescue operations. However, due to time constraints in urgent situations, accurately assessing the anchors’ pullout capacity can be challenging. Therefore, it is essential to develop models that can effectively calculate the pullout capacity of anchors to ensure cost-effective and safe applications.

“It is reasonable to consider small anchors as friction piles, as they transfer loads through friction between the soil and the anchor or pile surface when subjected to weight.”

Previous studies have developed various methods to predict pullout capacity, including empirical, numerical, and semi-analytical approaches. Empirical methods are based on field tests and take into account factors such as soil type, anchor diameter, rod displacement, and embedment length. Numerical methods, on the other hand, utilize specialized software to simulate different pullout processes without the need for field testing. However, these methods can encounter limitations, including numerical instability when addressing non-linear problems, as well as challenges related to adaptive meshes and complex boundary conditions. The semi-analytical methods combine analytical techniques with numerical analysis, offering a more refined and improved approach to understanding pullout capacity.

With the advancement of computational techniques, particularly in machine learning, the models developed have demonstrated enhanced accuracy and reliability compared to traditional methods. Researchers have employed various approaches, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Least Squares Support Vector Machines (LSSVM), ensemble learning, boosting techniques, and bagging, to create sophisticated models.

Notably, a study conducted by Lin Li et al. from China focused on predicting the pullout capacity of small anchors using a stacking machine learning technique. Stacking has gained significant traction among researchers due to its ability to leverage the strengths of individual models within an integrated framework, thereby improving prediction accuracy. The primary advantage of stacking lies in its potential to reduce variance, correct prediction errors, and enhance generalization. In this study, three machine learning algorithms—K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Support Vector Regression, and XGBoost—were utilized as base models within a linear regression framework.

The K-nearest neighbors (KNN) algorithm classifies data points by examining a specified number (K) of nearest neighbors in the feature space. In regression tasks, KNN identifies the K-nearest neighbors of a data point from the training dataset, averages their values, and uses this average as the predicted value for the new data point.

Support Vector Regression (SVR) is an extension of Support Vector Machine designed for regression tasks. Its main principle is to minimize the distance between a hyperplane and the furthest sample point. For nonlinear regression, SVR utilizes kernel functions to transform the data into a higher-dimensional space. The optimization process in SVR seeks to maximize the margin while minimizing overall loss, allowing for a wider error tolerance. Loss is calculated only when the predicted values fall outside an acceptable range of actual values.

XGBoost is an advanced machine learning model based on gradient-boosting trees. It combines multiple decision trees to capture nonlinear relationships and enhance predictive accuracy. Key features include regularization to prevent overfitting, customizable loss functions, and the ability to evaluate feature importance for better interpretability.

The dataset utilized in this study consists of 119 in-situ anchor pullout tests, accompanied by corresponding cone penetration data. After a thorough evaluation of six potential influencing factors, were identified, the anchor equivalent diameter, embedment depth, average tip resistance along the embedment depth, average sleeve friction along the embedment depth, and installation technique. The dataset was systematically divided into 80% for training and 20% for testing purposes. Furthermore, a K-fold cross-validation was employed to effectively partition the training set, ensuring that each fold comprises one validation set and K-1 training sets. This approach enhances the robustness of the model validation against unseen data and facilitates a more accurate estimation of its performance.

The performance of the model was assessed utilizing the R² metric. According to the results, the stacking techniques achieved an R² value of 0.93. In comparison to individual models, specifically the Support Vector Regression (SVR) with R² = 0.80, K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) with R² = 0.86, and XGBoost with R² = 0.89, the stacking method obtained the highest accuracy. Furthermore, the mean absolute error (MAE) was calculated for each model, resulting in SVR (MAE = 0.24), KNN (MAE = 0.22), XGBoost (MAE = 0.16), and Stacking (MAE = 0.15). Thus, this analysis confirms that the stacking method is the best-performing model with the least errors. Consequently, the proposed stacking model can be regarded as a dependable tool for estimating the pullout capacity of ground anchors based on the observed Cone Penetration Test (CPT) data.

The significance of the feature was assessed utilizing XGBoost. The findings indicate that, among the various factors, the average sleeve friction along the embedment depth exerts the greatest influence on pullout capacity, followed by embedment depth, anchor equivalent diameter, and installation technique. Conversely, the average tip resistance along the embedment depth demonstrates the least contribution.

In conclusion, the study of small anchor pullout capacity demonstrates the critical role that effective anchoring plays in ensuring the safety and stability of temporary structures during emergency situations. The integration of machine learning techniques, particularly the stacking method utilizing K-Nearest Neighbors, Support Vector Regression, and XGBoost, presents a significant advancement in accurately predicting pullout capacity. This approach not only enhances predictive accuracy but also alleviates the time constraints typically associated with urgent relief operations. By systematically analyzing influential factors and employing robust validation methods, the findings highlight the potential for these models to guide the selection and implementation of anchoring solutions in disaster response scenarios. Leveraging such innovative computational techniques can ultimately improve the reliability and effectiveness of emergency shelters, thereby better supporting affected communities during natural disasters.

Reference

Li, L., Zuo, L., Wei, G. et al. A stacking machine learning model for predicting pullout capacity of small ground anchors. AI Civ. Eng. 3, 11 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43503-024-00032-8

Littlejohn, G. (1980). Design estimation of the ultimate load-holding capacity of ground anchors. Ground Engineering, 13(8), 00174653.

Kim, N. K., Park, J. S., & Kim, S. K. (2007). Numerical simulation of grou-nd anchors. Computers and Geotechnics, 34(6), 498–507.

Deshmukh, V., Dewaikar, D., & Choudhury, D. (2010). Computations of uplift capacity of pile anchors in cohesionless soil. Acta Geotechnica, 5, 87–94.