Imagine you’re driving down a freshly paved road. It’s smooth, well-marked, and feels safe. Now imagine that same road five years later, cracked, uneven, and dotted with potholes. Keeping roads in good shape isn’t just about comfort; it’s about safety, efficiency, and cost. But before you can fix a road, you need to know exactly what’s wrong with it. That’s where modern technology like mobile laser scanning comes in, and where artificial intelligence is now making a huge leap forward.

In a recent study published in the Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering, researchers from Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas in Colombia presented a novel method for automatically extracting road surfaces from mobile LiDAR data using artificial neural networks (ANNs). Their approach achieved 99% precision and 99% recall after refinement, numbers that rival and even surpass many existing state-of-the-art methods. But what does that actually mean? And why does it matter for cities, drivers, and the future of infrastructure?

In this article, we’ll break down the science in simple terms, walk through how the method works, and explore what it could mean for the roads you use every day.

Why Road Surface Extraction Matters

Roads are more than just asphalt. They are complex assets that require constant monitoring. From detecting potholes and cracks to assessing overall roughness, engineers need accurate 3D models of road surfaces to plan repairs, ensure safety, and optimize budgets.

Traditionally, the process of conducting inspections and surveys relied on manual methods or semi-automated techniques, which can be time-consuming, costly, and occasionally hazardous. The introduction of Mobile Laser Scanning (MLS), also referred to as mobile LiDAR, has transformed this landscape. LiDAR sensors, mounted on vehicles, scan roadways and their surroundings to generate dense “point clouds“, comprising millions of 3D points that accurately represent all objects encountered by the laser, including road surfaces, curbs, signage, trees, and vehicles.

But here’s the catch: just having the data isn’t enough. You need to separate the road surface from everything else. That process is called road surface extraction, and until recently, it relied heavily on manual input, predefined road widths, or complex parameter tuning. That’s where AI comes in.

The Limits of Traditional Methods

Previous methods for road extraction often required prior knowledge, like the width of the road—or involved many steps of filtering and thresholding.

For example:

- Some methods used elevation filters first, then applied road-width assumptions.

- Others relied on scan-line analysis or density-based clustering, but still needed manual parameter adjustments.

These approaches worked well in controlled settings but struggled in complex urban environments where road widths vary, curbs are irregular, or obstacles like parked cars clutter the scene.

The Colombian research team asked: What if we could teach a neural network to recognize the road surface directly from the point cloud, without hard-coded rules?

How Neural Networks “Learn” a Road

Artificial neural networks are inspired by the human brain. They learn patterns from labeled examples. In this case, the “examples” are points in a LiDAR cloud labeled as road surface, ground (non-road), or non-ground (objects like cars, signs).

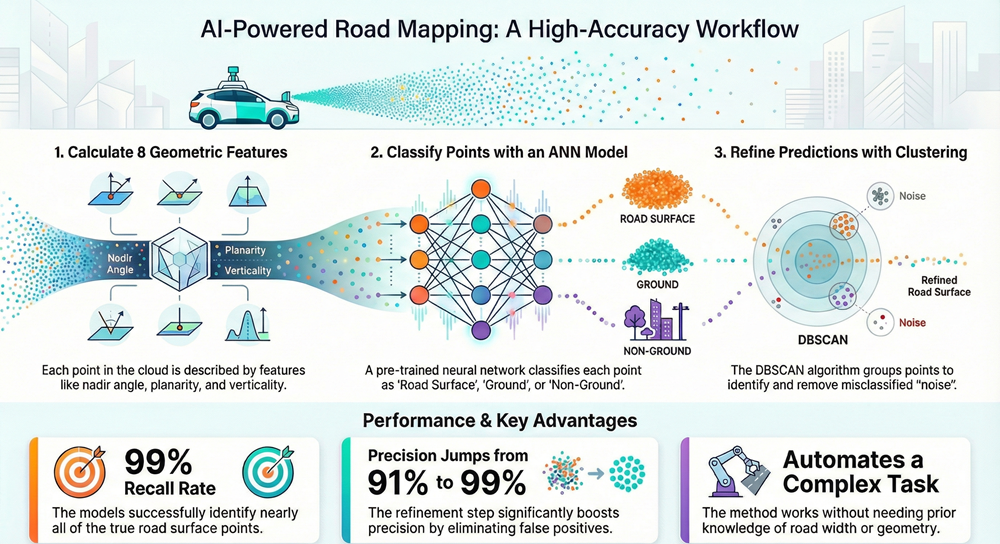

But what does the network actually “see”? Instead of images, it uses eight geometric features calculated for each point:

- Nadir Angle: Think of this as the “view angle” from the LiDAR sensor to the point. It helps the network understand the width and layout of the road.

- Normal Vectors (X, Y, Z): These describe the orientation of the surface at each point. Is it flat? Sloped? Vertical?

- Linearity, Planarity, Scattering: Known together as dimensionality, these describe the shape of the local neighborhood of points. Is it line-like? Plane-like? Or scattered like vegetation?

- Verticality: High for vertical objects like poles or building walls.

These features are cleverly chosen because they’re largely independent (low correlation), meaning each brings unique information to the network.

“Imagine you’re teaching someone to recognize a sidewalk. You might tell them: It’s usually flat (planarity), often beside a road (nadir angle helps locate it), and not covered in grass (scattering low) or poles (verticality high). The neural network learns similar rules, but through math.”

The Training Process: Two Architectures, One Goal

The team tested two types of neural networks:

- Feedforward Neural Network: A straightforward, layered network where data moves in one direction.

- LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) Network: More often used for sequences (like text or time series), but here applied to spatial data.

Both were trained on 6 million points from an urban scan of Paris, courtesy of the TerraMobilita/iQmulus benchmark dataset. The training took just 23–34 minutes on a consumer-grade laptop with a GPU.

The results? Both networks learned quickly, reaching over 98% accuracy within a few epochs (training cycles). The LSTM had a slight edge in final accuracy (99% vs. 98.25%), but overall, their performance was remarkably similar.

The “Oops” Moments: Where the Network Got Confused

Even the best models make mistakes. In initial predictions, about 9% of points classified as “road surface” were actually noise, mostly sidewalks or flat ground areas mistaken for road. Why? Because sidewalks and roads share similar geometric features: both are flat, horizontal, and smooth.

The confusion matrices revealed:

- Road surface recall: 99% (almost all road points were found).

- Ground recall: ~75% (many sidewalk points were mislabeled as road).

- Non-ground recall: 98% (objects like cars and signs were well identified).

This is where refinement came in.

The Clean-Up Step: DBSCAN Clustering

DBSCAN is a clustering algorithm that groups points based on density. Misclassified points (noise) tend to be isolated or form small clusters, while the true road surface is one large, connected group.

By tuning two parameters, epsilon (maximum distance between points) and minimum points per cluster, the team removed nearly 90% of the noise, boosting precision from 91% to 99% without losing recall.

“Imagine you’ve spilled salt and pepper on a dark table. The salt (road) is the majority; the pepper (noise) is scattered. DBSCAN helps you blow away the pepper while keeping the salt.”

Why This Approach Is a Big Deal

- Minimal Human Intervention: Unlike earlier methods, this one doesn’t require road width or complex parameter tuning.

- Speed and Scalability: Training is quick, and the model can be reused in similar urban environments.

- High Accuracy: 99% precision/recall matches or beats many published methods.

- Practical Output: The final road surface is clean, well-defined, and ready for use in pavement analysis, crack detection, or 3D mapping.

Limitations and the Road Ahead

The method isn’t perfect. It assumes the presence of curbs and well-defined road edges, which may not exist in rural or unstructured environments. It also relies on sensor position data to compute the nadir angle, without that, the model’s performance could drop.

Future work could explore:

Domain adaptation involves making pre-trained models applicable to various road types without the need for retraining. This can be enhanced through integration with advanced deep learning models like KPConv or RandLA-Net, which provide more precise segmentation. Additionally, achieving real-time processing is crucial for applications in autonomous vehicles and continuous road monitoring, ensuring timely and efficient data analysis.

Conclusion

What the Colombian team has shown is that you don’t always need the most complex AI model to solve a real-world problem. Sometimes, a well-designed feature set and a simple neural network—paired with smart refinement, can achieve stunning results.

For city planners, this means faster, cheaper, and more accurate road surveys. For engineers, it means better data for maintenance planning. And for the rest of us, it means safer, smoother roads in the long run.

As AI continues to learn how to “see” and interpret our built environment, studies like this remind us that the most impactful innovations often come from clever applications of existing tools, not just from chasing the newest algorithms.

Reference:

- López-Pinzón,S. Daniel and Fernández-Gómez,W. Darío (2026). ANN-Based Approach for Road Surface Extraction from Mobile LiDAR Point Clouds. (e227343). Journal of Soft Computing in Civil Engineering, 10(2), e227343 doi: 10.22115/scce.2025.1912

- Le, T., Hassan, F., Le, C., & Jeong, H. D. (2022). Understanding dynamic data interaction between civil integrated management technologies: a review of use cases and enabling techniques. International Journal of Construction Management, 22(6), 1011-1032.

- Zai, D., Li, J., Guo, Y., Cheng, M., Lin, Y., Luo, H., & Wang, C. (2017). 3-D road boundary extraction from mobile laser scanning data via supervoxels and graph cuts. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 19(3), 802-813.