Imagine a world where every drop of wastewater is meticulously analyzed, treated with precision, and even turned into valuable resources, all without human error or massive energy waste. This isn’t a distant dream. Thanks to Artificial Intelligence (AI), it’s becoming today’s reality in wastewater treatment plants worldwide.

In this article, we’ll explore how AI is revolutionizing an industry critical to our health and environment. We’ll break down the complex technologies, share real-world success stories, and look at the challenges and incredible opportunities ahead.

Why Wastewater Treatment Needs a Tech Upgrade

First, let’s understand the scale of the problem. According to the United Nations, over 80% of the world’s wastewater flows back into rivers, lakes, and oceans without proper treatment. That’s a staggering amount of pollutants, from household chemicals and pharmaceuticals to industrial waste and microplastics, entering our ecosystems.

Traditional treatment plants, while effective, have major drawbacks:

- High Energy Consumption: Aeration (pumping oxygen into wastewater) alone can consume 50-60% of a plant’s total energy.

- Chemical-Intensive Processes: Coagulation and disinfection often rely on large, sometimes imprecise, doses of chemicals.

- Reactive, Not Proactive: Operators often respond to problems (like a spike in toxins) after they occur, rather than predicting and preventing them.

- Inability to Handle “Emerging Contaminants”: New pollutants like pharmaceuticals, endocrine disruptors, and microplastics are hard to detect and remove with conventional methods.

This is where AI steps in. It’s not about replacing human expertise but augmenting it with superhuman data-crunching abilities, 24/7 monitoring, and predictive power.

How AI is Transforming the Treatment Process: The Technical Toolkit

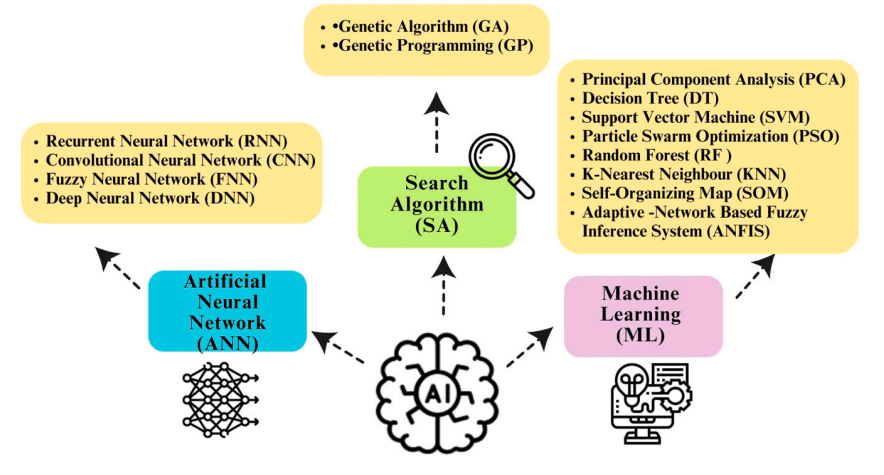

The research highlights several AI families, each with unique strengths for different tasks in a treatment plant. Think of them as specialized tools in a smart toolbox.

1. Search Algorithms: The Optimizers

These are problem-solving engines that find the best possible solution from countless options.

- Genetic Algorithm (GA): It is a computational method inspired by the principles of natural selection, seeking to “evolve” optimal solutions over successive generations. It shines particularly in the realm of multi-objective optimization. For instance, in practical applications, GA has been utilized to optimize chemical dosing and aeration rates to achieve the dual goals of reducing costs while simultaneously improving effluent quality. A notable full-scale study demonstrated the effectiveness of GA by minimizing an Effluent Quality Index, showcasing its real-world applicability. However, one significant drawback of GA is that it can be computationally intensive and may become trapped in “local optima,” which refers to a solution that is satisfactory but not the absolute best possible outcome.

- Genetic Programming (GP): It is a method related to Genetic Algorithms (GA) that focuses on evolving entire program structures to model complex relationships. One practical application of GP is in predicting the performance of a Membrane Aerated Biofilm Reactor (MABR) under various conditions, thereby assisting in understanding the relationship between inputs, such as ammonia, and outputs. However, a notable drawback of GP is that it is primarily utilized in laboratory or pilot studies, as it often struggles with the vast and noisy data generated by full-scale plants.

2. Machine Learning (ML): The Predictors & Pattern-Finders

Machine learning (ML) algorithms learn from historical data to make predictions and reveal hidden patterns.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): It reduces complex datasets with many variables, such as pH, conductivity, and chemical oxygen demand, into a few key components; in a full-scale plant in Nicosia, PCA helped identify core relationships among water quality parameters, improving monitoring efficiency, though it works only for linear relationships and may lose some information.

- Decision Trees (DT) and Random Forests (RF): These techniques use rule-based structures to make predictions, with RF combining many trees for better stability; they have been used to predict odour levels and forecast Fat, Oil, and Grease (FOG) in wastewater, but they can overfit and perform poorly on new data.

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): It is effective for classification and regression, especially with small datasets, and are used for fault detection in plants to separate normal sensor behavior from failures, though they struggle with very large datasets.

- Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): PSO is inspired by bird flocking, is a strong optimization method used to identify key parameters in activated sludge processes, helping build digital twins of biological reactors for improved control.

3. Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) & Deep Learning: The Heavy Lifters

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and deep learning models represent the heavy lifters of modern data-driven modeling, drawing inspiration from the structure and functioning of the human brain to uncover complex, non-linear relationships within large and heterogeneous datasets.

Among these, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their advanced variant, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, are particularly well suited for time-series applications due to their inherent memory mechanisms, enabling them to capture temporal dependencies in historical data. In wastewater treatment systems, these models have been successfully applied to predict short-term effluent quality, such as next-day or next-week concentrations of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) and total suspended solids (TSS), with studies like those conducted at the Nine Springs treatment plant demonstrating high predictive accuracy.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), on the other hand, excel in analyzing image-based and spatial data and are emerging as powerful tools for automated microplastic detection. Future-oriented research, including the PlasticNet project, employs CNN-based image analysis of micro-FT-IR imagery to identify and quantify microplastic particles in wastewater, significantly reducing the time and effort associated with manual inspection; however, the effectiveness of CNNs is constrained by the limited availability of large, labeled image datasets in wastewater research.

To address uncertainty and imprecision in real-world plant operations, Fuzzy Neural Networks (FNNs) and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference Systems (ANFIS) integrate the pattern-learning capabilities of neural networks with fuzzy logic’s human-like reasoning, making them particularly effective for modeling energy consumption, effluent quality in activated sludge systems, and the optimization of saline wastewater treatment processes.

Finally, Deep Neural Networks (DNNs), characterized by multiple hidden layers and their ability to perform automatic feature extraction, have demonstrated exceptional performance in handling high-dimensional operational data, with full-scale studies reporting prediction accuracies exceeding 92% for final effluent quality, highlighting their robustness and scalability for complex wastewater treatment applications.

Real-World Case Studies: AI in Action

- Cuxhaven, Germany: A WWTP implemented AI-driven aeration control, reducing aeration energy consumption by 30%. The AI predicts the optimal oxygen levels needed in real-time, avoiding waste.

- Marselisborg, Denmark: This plant uses dynamic process optimization with AI to not only meet treatment standards but also become a net energy producer, generating more biogas from sludge than it consumes.

- San Francisco, USA: The city’s utilities use AI for smart water management, leading to reduced chemical use, lower operational costs, and fewer system downtimes through predictive maintenance.

- Singapore: The OREX™ system uses AI to optimize anaerobic digestion, maximizing biogas production and turning waste into a renewable energy source.

The Crucial Challenge: Detecting “Contaminants of Emerging Concern” (CECs)**

One of the most critical points discussed in this study is the urgent need for innovative solutions to address a modern environmental crisis: Contaminants of Emerging Concern (CECs). These substances are pollutants that have only recently been acknowledged for their hazardous impacts, even when present in extremely low concentrations. Examples of CECs include:

- Pharmaceuticals: This group encompasses a broad range of substances, including widely used medications such as painkillers, antibiotics, and hormones, all of which can accumulate in water sources and pose significant risks to both human health and aquatic ecosystems.

- Personal Care Products: Common items such as sunscreens, fragrances, and various cosmetics often contain chemicals that are harmful to the environment. These substances can enter water supplies through daily use and improper disposal.

- Endocrine Disruptors: Chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) fall into this category, which can interfere with hormonal functions in wildlife and humans. Their widespread presence in plastics and other materials makes them particularly challenging to manage.

- Microplastics: Tiny plastic particles that result from the degradation of larger plastic items are ubiquitous in our environment. They pose a serious threat as they can absorb and carry other harmful pollutants.

Traditional wastewater treatment facilities are not equipped to effectively remove these emerging contaminants, as they were designed for different types of pollutants. Furthermore, current detection methods often rely on expensive and time-consuming laboratory tests, which can delay timely responses.

In contrast, artificial intelligence (AI) presents a transformative opportunity in this area. By leveraging advanced techniques, AI can enhance the detection and monitoring of CECs in real time. For instance, algorithms can be trained on spectral data obtained from Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) sensors, as well as from microscopic images. These models can learn to identify the unique “fingerprints” of these pollutants, facilitating a more proactive and dynamic approach to wastewater management.

This capability allows operators to make on-the-fly adjustments to treatment processes, significantly improving the removal efficiency of these contaminants. The development of innovative tools such as PlasticNet represents just the start of what could be a paradigm shift in environmental monitoring and management, highlighting the critical role of AI in tackling these pressing environmental issues.

Conclusion

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is far from being a mere magic wand; rather, it stands as one of the most powerful tools available to modernize and enhance our aging water infrastructure, particularly in addressing the complex challenges of the 21st century. With its ability to analyze vast quantities of data rapidly, AI is transforming wastewater treatment processes in several significant ways.

One of the most notable advancements is the reduction of energy consumption and operational costs. By optimizing the processes involved in wastewater treatment, AI systems can identify inefficiencies and suggest improvements, leading to substantial savings for municipalities and industries. In addition to cost savings, AI’s capabilities extend to detecting invisible micropollutants that often elude conventional monitoring methods. This not only ensures higher water quality but also protects ecosystems and public health by addressing contaminants that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Moreover, the integration of AI in wastewater management aligns seamlessly with global initiatives, such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). This goal advocates for universal access to safe and affordable drinking water, improved sanitation and hygiene, and sustainable water resource management. By transforming raw data into actionable insights, AI aids in ensuring that every drop of treated water returned to the environment is significantly cleaner, while also maximizing the value of the resources extracted from wastewater.

The journey towards a revitalized and more sustainable approach to water management has already begun. As AI technology continues to evolve and be implemented in water treatment facilities worldwide, the potential for a healthier planet is not only achievable but is already flowing through our pipes. The possibilities are vast, promising a future where water infrastructure is more resilient, efficient, and capable of meeting the needs of generations to come.

Reference

- Jaganathan, J. S., Ali, J. M., & Abdullah, S. R. S. (2025). Unlocking the potential of artificial intelligence in wastewater treatment: Innovations, opportunities, and challenges. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering, 13(6), 119671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jece.2025.119671